Why Your Health Strategy Fails: 4 Archetypes Explained

I've spent the last decade watching patients apologize for things that aren't actually problems.

"I'm sorry, I know I should just be able to do this."

"I'm sorry, I don't know why this is so hard for me."

"I'm sorry, I just can't seem to get it together."

They say this while sitting across from me with long track records of remarkable accomplishments at home, in communities and at work. Business owners who've built seven-figure companies. Doctors, lawyers, accountants, and engineers who've mastered complex systems. Women who've raised children, managed teams, and navigated intricate processes with precision. And yet when it comes to their own health, they arrive in my office convinced they're uniquely broken.

The apologies always come before the history, before I've even asked a question.

What I've learned is that the apology isn't about laziness or lack of effort. It's about years of trying to force their brains to work in ways they simply don't. They've been handed the same generic advice everyone gets: eat less, move more, find your motivation. And when it doesn't stick, they've been told the problem is them.

These women aren't failing because they lack discipline or intelligence. They're failing because they're using strategies designed for a completely different nervous system than the one they actually have.

The physician who can't stick to a meal plan? She doesn't need more nutrition information. She needs to understand why her brain requires novelty to maintain engagement, and why the same breakfast every morning makes her want to set her kitchen on fire.

The executive who knows exactly what to do but can't seem to start? She doesn't need another app or accountability partner. She needs to recognize that her brain doesn't perceive routine tasks as urgent enough to prompt action, and that she's mistaken a neurobiological pattern for a character flaw.

This isn't about motivation or discipline. It's about alignment.

And once you understand your specific pattern (the way your particular nervous system approaches change) everything shifts. Not because you suddenly develop willpower you didn't have before, but because you stop fighting your own wiring.

This is for the woman who has tried everything and has blamed herself when it didn't work. If you've ever felt like everyone else got an instruction manual you somehow missed, this is for you.

The information isn't the problem.

You know what to eat. You understand that movement matters. You've read the articles, listened to the podcasts, maybe even hired the nutritionist.

And yet here you are again.

Not because you're lazy. Not because you lack discipline or intelligence. You've built businesses, raised children, and managed complex lives with competence and precision. The idea that you can't figure out how to eat better doesn't even make sense when you look at everything else you've accomplished.

The problem isn't information. It's alignment.

Researchers call this the intention-behaviour gap: the frustrating disconnect between what we plan to do and what we actually do. Studies show that intentions alone predict only about 30-40% of actual behaviour. The rest? That's where strategy comes in. And not just any strategy. The right strategy for your particular brain.

Most health advice assumes everyone struggles for the same reasons and therefore needs the same solutions. Eat less, move more, find your motivation, repeat until it works. When it doesn't work (and it often doesn't), the only explanation offered is that you didn't try hard enough.

That's not clinical precision, but instead lazy thinking dressed up as discipline.

What actually blocks sustainable change varies dramatically from person to person. The woman who can't seem to get started faces an entirely different obstacle than the one who starts strong but loses steam. The one drowning in perfectionism needs different tools than the one who's been running herself empty for decades.

Understanding your specific pattern changes everything.

Not willpower, wiring

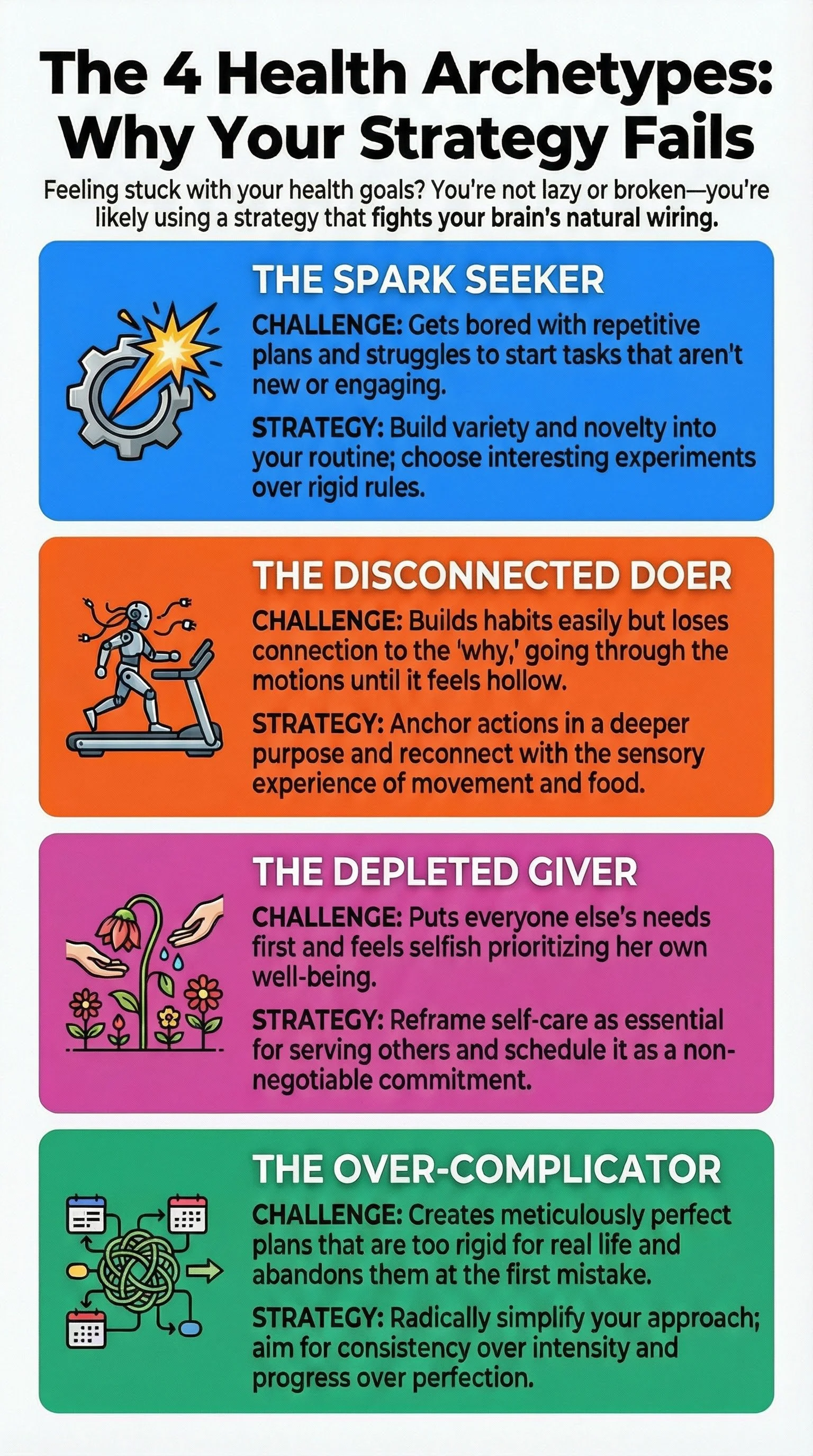

In my clinical work at The Shift Clinic, I see four distinct patterns that keep accomplished women stuck. These aren't personality types or fixed categories. They're operating patterns: ways your nervous system has learned to approach change based on your unique cognitive architecture and history.

You'll recognize yourself in more than one. Most people have a primary pattern that runs the show, with others showing up in specific contexts. The goal isn't to label yourself, but to understand what you're actually up against.

Think of them as different navigation systems. Some people need detailed turn-by-turn directions. Others do better with a general sense of direction and the freedom to find their own route. Neither is better or worse. But if you're trying to use GPS when what you actually need is a compass, you'll feel lost no matter how hard you try.

Because you cannot willpower your way through a mismatch between your strategy and your psychology, you need to choose approaches that work with your neurobiology, not against it.

When the engine won't turn over

Here's what most people miss: it's not just about choosing different tactics and objectives. It's about picking different types of tactics and objectives. Different structures, different frequencies, different levels of flexibility.

At The Shift, every patient builds their own strategy across three domains: Metabolism, Appetite, and Perspective. We call it the MAP framework. Within each domain, you choose specific tactics (the small, concrete actions you'll take) paired with objectives that define what success looks like. But the architecture of those tactics and objectives needs to match how your brain actually processes change.

The Spark Seeker needs tactics with built-in variety and objectives that allow multiple pathways to success. The Disconnected Doer needs tactics that reconnect to sensory experience and objectives anchored in forward-looking purpose. The Depleted Giver needs tactics that reframe self-care as service and objectives that are non-negotiable. The Over-Complicator needs tactics so simple they feel almost ridiculous and objectives with flexibility built in from the start.

Same framework. Completely different execution.

The Spark Seeker

I had a patient once (brilliant software engineer, ran a team of thirty people) who came to me in tears because she couldn't stick to a meal plan for more than three days.

"I don't understand," she said. "I can manage complex projects with dozens of moving parts. Why can't I just follow a simple eating schedule?"

Because her brain doesn't work that way. And there's nothing wrong with that.

Some people struggle most with getting started. Not because they're unmotivated. Quite the opposite. They often feel intense enthusiasm for new projects and genuine excitement about change. But then something happens between the idea and the execution.

Traditional, repetitive plans feel like anchors. Detailed meal prep systems create overwhelm. The more rigid the structure, the less likely follow-through becomes.

This isn't a character flaw.

It's how the brain processes tasks that require novelty and stimulation to drive action. Neuroscience research points to differences in dopaminergic signaling that affect task initiation. For some people, the brain requires higher levels of external stimulation to reach optimal activation. Without that spark, they experience what researchers describe as a state in which the brain knows what to do but cannot initiate the required physical movement.

If this sounds familiar, your brain performs better when tasks are interesting, engaging, or novel. The effort required to initiate and organize can feel genuinely insurmountable. Not because you're weak, but because your neurobiology responds differently to stimuli.

In The Shift framework, we call this the need for tactics that pass the Four Yeses. Small actions you'd actually want to do. Entry points so low that resistance doesn't have time to build—a launch pad, not a master plan.

My software engineer? We threw out the meal plan entirely. Instead, we built what I call a "curiosity menu": a rotating list of interesting food experiments she actually wanted to try. New restaurants. Unfamiliar vegetables. Recipes that felt like projects rather than chores. Her nutrition improved dramatically, not because she developed discipline, but because we stopped asking her brain to do something it wasn't designed for.

For the Spark Seeker, tactics need to be inherently interesting or challenging. Not repetitive. Think: try a new restaurant each week instead of meal-prepping the same thing; explore a different walking route daily instead of the same gym routine; and experiment with unfamiliar ingredients instead of following a rigid protocol.

And objectives? They need options built in. Not "eat protein at breakfast" but "choose one of five protein-rich breakfasts that sound appealing today." Not "work out Monday, Wednesday, Friday" but "move your body three times this week in ways that feel engaging." The structure provides direction without becoming a cage.

For the Spark Seeker, performance transforms when tasks become more salient and stimulating. Not more disciplined.

When autopilot becomes a prison

The Disconnected Doer

Other people have no trouble building habits. They can adopt a new routine almost immediately and integrate it into daily life with impressive consistency. Morning workouts, meal timing, supplement regimens: the behavioural architecture goes up fast.

But then something shifts.

The routine becomes automatic, which sounds like success but often isn't. They're going through the motions without connection to why any of it matters—checking boxes. Spinning wheels. Following a program that technically works but feels increasingly hollow.

I see this pattern in high-performers who've spent years optimizing their lives into efficient systems. They wake up at 5 AM because that's their routine. They track macros because that's the protocol. They follow the plan because, well, because it's the plan.

And then one day they're sitting in my office saying, "I'm doing everything right. Why do I feel so empty?"

The danger here isn't starting. It's losing touch with purpose.

This pattern emerges when behaviour control transfers from goal-directed to habitual systems. Research shows these are distinct neural processes. One is sensitive to current values and outcomes; the other runs on autopilot, relying solely on contextual cues. The habitual system is efficient but inflexible. It keeps firing even when the behaviour no longer serves you.

This explains why the Disconnected Doer can continue a routine they no longer enjoy, simply because it's "what they do." And why disruptions to context (travel, a new job, a relocated gym) can collapse entire health systems overnight. The habits were cued by the environment rather than anchored in values.

At The Shift, we start with values work for precisely this reason. Not the values you inherited or think you should have, but the ones that actually drive your choices when no one's watching. When your daily actions connect to a vivid picture of who you're becoming, the same habits feel entirely different.

True vitality doesn't come from perfect execution. It emerges when your actions link to a forward-looking purpose.

For the Disconnected Doer, tactics need to reconnect to sensory experience and meaning. Not just "go to the gym" but "move in ways that make you feel powerful." Not "eat vegetables" but "notice how your body feels two hours after a meal rich in fibre and colour." The tactic itself must include the why.

And objectives? They need to point toward something beyond the action itself. Not "lose 20 pounds" but "build the energy to be fully present with my kids." Not "work out four times a week" but "develop strength that lets me feel capable in my body." The objective becomes a north star, not a checkbox.

I had a patient who'd been doing CrossFit five days a week for three years. Perfect attendance. Impressive strength gains. And absolutely miserable. When we dug into her actual values, fitness wasn't even in her top five. What mattered to her was creativity, connection, and being present with her kids.

We didn't add more workouts. We redesigned her entire approach around what she actually cared about. Now she moves her body in ways that feel like play rather than obligation. And her kids join her.

When everyone else comes first

The Depleted Giver

Then there's the pattern I see most often in my practice: the woman who has spent decades putting everyone else first.

She's dependable. Responsible. The person everyone calls when things fall apart. Her values around service, availability, and caretaking aren't wrong. They've made her exceptional at her work and indispensable to her family.

But those values have been unchecked for years, while her well-being has waited in line.

Now, at midlife, when her body is finally demanding attention, choosing herself feels like abandoning everyone else.

I had a patient (a family physician, actually) who came to me twenty pounds heavier than she wanted to be and completely exhausted. She knew exactly what to do. She'd been prescribing these interventions to patients for years. But when it came to her own health, she couldn't seem to prioritize it.

"I feel selfish," she told me, "taking time for myself when my patients need me, when my kids need me. When my aging parents need me."

I asked her what would happen if she kept running on empty.

She knew the answer. She'd seen it in her own practice a hundred times. Burnout. Resentment. Eventually, collapse. And then she wouldn't be available to anyone.

Psychologists call this pattern sociotropy: an excessive investment in relationships and a strong need for approval. For the Depleted Giver, health behaviours are performed for external validation rather than internal alignment. The decision-making calculus always weighs others' needs above her own.

The barrier here isn't knowledge or skill. It's a values conflict operating beneath conscious awareness. She's waiting for permission to prioritize her own needs, often from an external signal like a health scare or a direct plea from someone she loves.

For this pattern, strategy becomes an act of radical self-inclusion. Not abandoning responsibility, but recognizing that unlimited availability isn't actually serving anyone. Understanding that the flight attendant instructions were right: you do need to secure your own oxygen mask first.

So I gave her permission, not as her doctor, but as someone who has seen this pattern destroy too many brilliant women.

For the Depleted Giver, tactics must explicitly reframe self-care as service to others. Not "take a walk for yourself" but "build the energy your family needs you to have." Not "prioritize sleep" but "rest so you can show up fully for the people who depend on you." The tactic itself needs to resolve the values conflict.

And objectives? They need to be non-negotiable and scheduled with the same priority as other commitments. Not "try to exercise when I have time" but "movement is on my calendar Tuesday and Thursday at 6 AM, just like patient appointments." The objective becomes a commitment you keep, not a wish you hope for.

You are allowed to include yourself in the circle of people who deserve care.

You cannot hate yourself into health. And you cannot guilt yourself into sustainable change. But you can permit yourself to matter as much as everyone else you're taking care of.

When perfect becomes the enemy of possible

The Over-Complicator

Finally, there's the person who creates elaborate, meticulously researched plans that are too demanding to maintain.

Weeks of research. The optimal program. Every detail accounted for. And then one deviation (one missed workout, one unplanned meal) and the entire structure collapses.

Because if it's not perfect, what's the point?

I see this in the women who come to me with colour-coded spreadsheets and detailed protocols they've assembled from dozens of sources. They've read all the research. They know the optimal macros, the best supplements, and the most effective workout splits. Their plan is flawless.

And completely unsustainable.

This isn't really about wanting the best approach. It's maladaptive perfectionism creating psychological fragility. When success requires flawless execution, any imperfection triggers cascading self-criticism and often complete abandonment.

Researchers distinguish between adaptive perfectionists (who set high standards but remain resilient) and maladaptive perfectionists who equate self-worth with flawless achievement. The Over-Complicator lives in "all-or-nothing" thinking: any outcome less than 100% feels like total failure. This leads to cycles of overcommitment and burnout, where extreme intensity meets inevitable deviation, which the catastrophizing mind interprets as proof the entire project is ruined.

Our culture glorifies complex protocols and intense optimization. But for many women, the most effective path is the simplest one. Not the A+ week that leads to burnout, but the B+ week that actually compounds over time.

I had a patient who would start a new health protocol every few months. Each one was more complex than the last. Intermittent fasting with specific eating windows. Macro tracking down to the gram. Supplement stacks that required a spreadsheet to manage. And each time, within weeks, something would go wrong. A business trip. A sick kid. One meal that didn't fit the plan.

For the Over-Complicator, tactics need to be so simple they feel almost ridiculous. Not "track macros to the gram" but "notice if your plate has protein, fiber, and color." Not "follow a six-day training split" but "move your body for 20 minutes, any way that feels good." The tactic must allow imperfection from the start.

And objectives? They need flexibility built into the definition of success. Not "complete all five workouts this week" but "move at least three times, and if life happens, two still counts." Not "follow the meal plan perfectly" but "make choices aligned with your values 80% of the time, knowing 80% is excellent." The objective itself permits you to be human.

And she'd quit entirely.

Not because the plan was bad. Because it was too good. Too perfect. Too rigid to survive contact with real life.

In The Shift System, we work with tactics so small they feel almost ridiculous. The minimum viable action you can take on a difficult day is to maintain momentum rather than abandoning all effort. Consistency over intensity. Progress that doesn't require perfection.

The goal isn't a perfect plan. It's flexible consistency with whatever life actually looks like.

Finding your pattern

Most of us struggle not because we're lazy or uninformed, but because we're using tools that don't match how our brains actually work.

The Spark Seeker needs novelty and low friction, not detailed plans. The Disconnected Doer needs values reconnection, not more habits. The Depleted Giver needs permission structures, not productivity hacks. The Over-Complicator needs radical simplification, not better optimization.

You likely see parts of yourself in more than one pattern. That's normal. But there's usually a primary obstacle running the show right now: the one creating the most friction between your intentions and your actions.

Understanding why you get stuck is more potent than finding another meal plan or workout program. With that insight, you stop fighting your own nature and start building practices that actually fit.

The strategy you actually need

Self-awareness matters, but it's not enough on its own.

Understanding your pattern is the first step. The next step is building the specific tactics and objectives that work with your wiring, not against it.

That's exactly what the quiz (coming soon) does. It identifies your primary pattern and provides a personalized report outlining the tactics and objectives most likely to drive traction for your specific brain. Not generic advice. Not another one-size-fits-all protocol. The actual structure of your strategy needs to work.

Because sustainable change isn't about trying harder.

It's about trying differently, with a framework that accounts for who you actually are.

The destination hasn't changed. You still want to feel better in your body, to have more energy, to stop fighting yourself every day. But the route you take to get there? That needs to match how you actually move through the world.

Not how you think you should move. How you actually do.